By: Rev. Thomas Macdonald, Vice Rector

It would be hard to find a class of people more aware of their mortality than soldiers in wartime. The searing consciousness that one’s life might end at any moment leaves a mark on the veteran’s soul, one that endures long after hostilities have ceased and mortal danger has subsided. This burden that combat veterans carry is part of what we will acknowledge and honor this Friday on Veterans Day.

Of all the soldiers in all the wars in humankind’s long history of violence, I think the soldiers of the war that Veterans Day originally commemorated were immersed in death in an especially overwhelming way. While all war is terrible, World War I was especially so. In that “war to end all wars,” millions of men lived, fought, and died in ditches dug into the earth. In English we call those ditches “trenches,” thus the term “trench warfare.” In German, however, the term for this form of combat is known as Grabenkrieg, which literally means “grave warfare.” This term captures the horror unique to the Great War. The soldiers of that war lived day in and day out in open graves. Death was all around them all the time.

To say that this collective experience darkened the soul of Christian Europe would be a gross understatement. All the destructive “isms” of the 20th century—fascism, communism, nihilism—can be traced to the living death that a whole generation endured fighting Grabenkrieg. Faced with so much destruction and decay, many veterans turned to these ideologies to relieve their anguish and give them some semblance of hope and meaning in their shattered lives. Others embraced an occultism and spiritualism that promised to bridge the chasm between life and death.

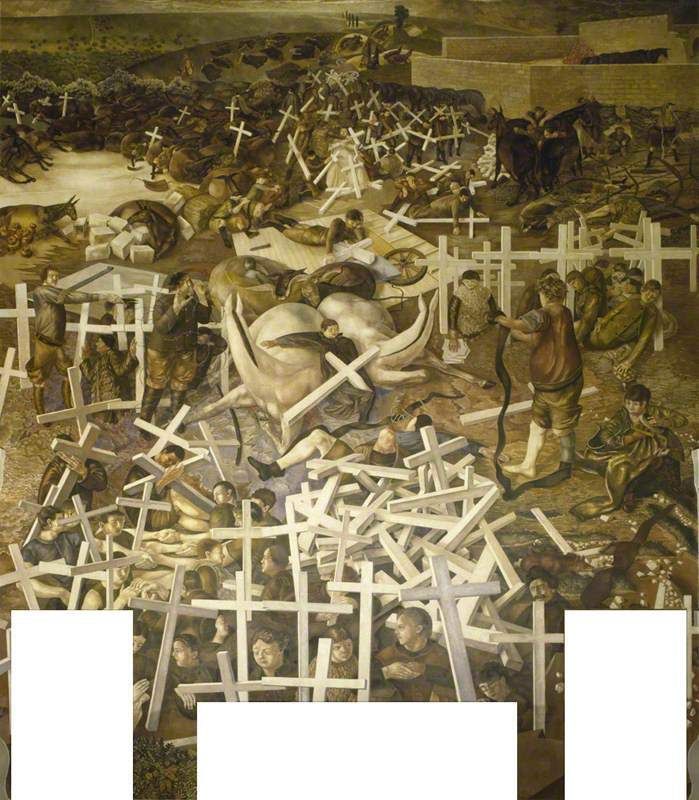

One veteran who resisted these trends was the English painter, Stanley Spencer. His experience in the trenches did not plunge him into the ideologies of despair that consumed so many of his contemporaries—quite the contrary. His experience of life in an open grave instead inspired in him what would become the defining theme of his art: the resurrection of the dead. Spencer spent the rest of his life painting enormous canvases depicting graveyards brimming with vital joy as the newly resurrected emerge from their tombs, embracing one another and resuming the affectionate gestures that knit them together in life. In one mural, he even transforms the mass graves of the Western Front into a scene of bewildered reversal as the resurrected soldiers find heaven come down to redeem what was once their hell. A steady stream of them marches toward Christ to offer Him the white wooden crosses that marked their graves.

Spencer’s paintings showcase the contemporary power of what inspired the Maccabean martyrs so long ago. They show the beauty of what Christ reveals as our destiny: our bodies, like His, will rise from the earth. We do not live just to fall into the grave.

We may not have endured anything like what the veterans of World War I experienced in the trenches, but the heaviness of a life overshadowed by death falls upon us all at some point or another. That heaviness has the power to crush us. To overcome this danger, on every Sunday and Solemnity, we profess our faith in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Faith in the resurrection not only fills our future with the hope of rising from the grave. It also gives us the capacity to live joyfully in the present. It enables us here and now to rise from the trials and traumas we have endured. Death comes long before the heart stops beating to those who live without hope. Eternal life can likewise dawn in us today if we live in the light that unknown day and unknown hour when graves will turn into gardens.